Guide to Mechanical Engineer Training: Skills, Education, and Career Paths

Mechanical engineer training can include accredited degrees, structured workplace learning, and focused short courses that build specific tools and methods. The right mix depends on your target role, the industries you want to work in, and how quickly you need practical capability. This guide breaks down common training routes, the core skills mechanical engineers develop, and how those skills connect to real workforce expectations across design, manufacturing, testing, and operations worldwide.

Mechanical engineering sits at the intersection of physics, materials, and real-world constraints like safety, cost, time, and maintainability. Training is most effective when it builds not only technical knowledge, but also the habits engineers rely on daily: documenting assumptions, checking results for plausibility, and communicating trade-offs clearly. Because the field spans many industries, a structured plan helps you progress from fundamentals to credible job-ready capability.

Mechanical engineer training programs

Mechanical engineer training programs typically fall into three buckets: formal education, structured workplace learning, and modular upskilling. Formal routes include associate degrees, bachelor’s degrees, and graduate study, usually covering core subjects like statics, dynamics, mechanics of materials, thermodynamics, fluids, and controls. These programs often include labs and team projects that mirror engineering workflows such as requirements definition, prototyping, and design reviews.

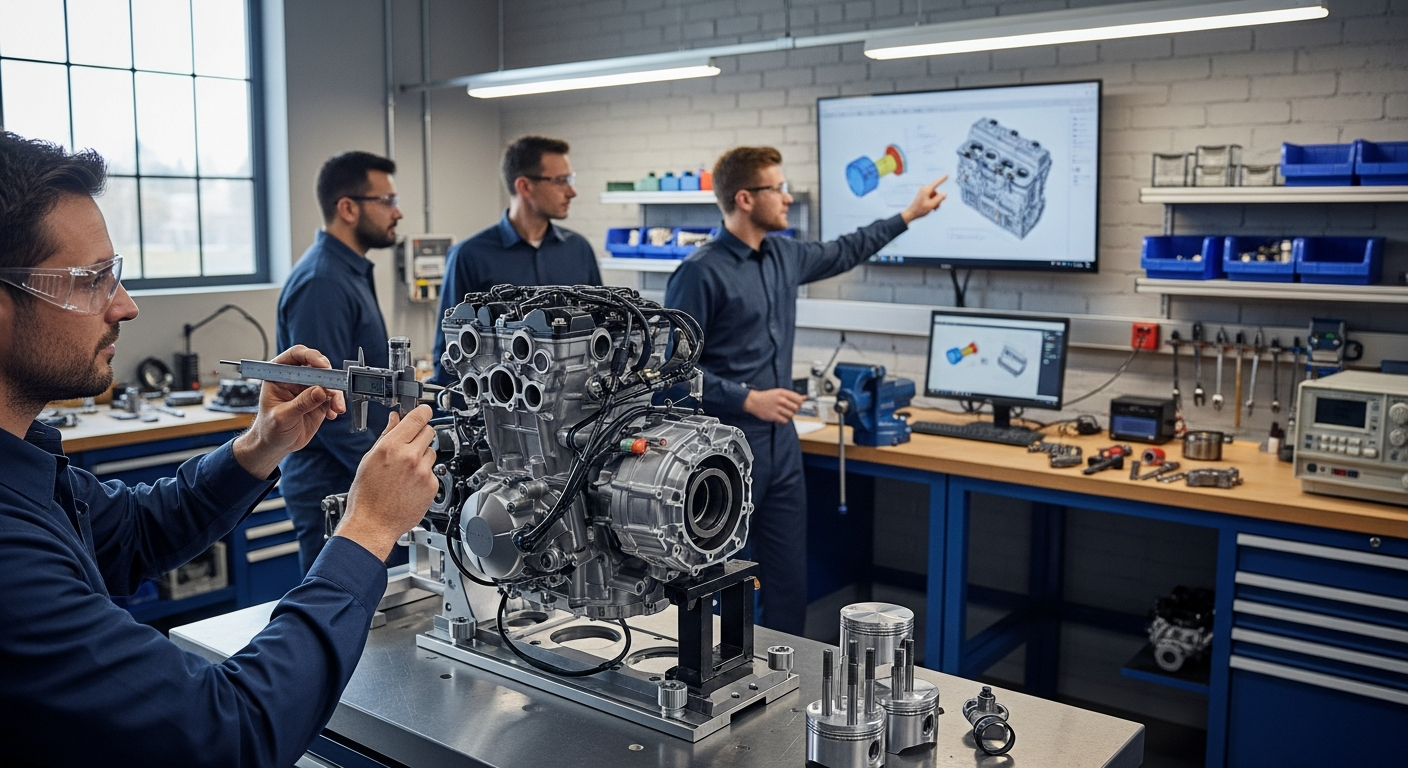

Workplace-based routes include apprenticeships, internships, cooperative education placements, and graduate development programs. Their main advantage is context: you learn how engineering decisions are made under standards, deadlines, and cross-functional collaboration with manufacturing, quality, procurement, and safety teams. Modular learning includes short courses and certificates focused on tools (CAD, FEA, GD&T) or methods (DFMEA, test planning), which are useful for filling gaps or switching industries.

When comparing mechanical engineer training programs, focus on outcomes rather than labels. Look for evidence of hands-on practice (labs, design-build projects, capstones), feedback loops (graded reports, design critiques), and exposure to engineering documentation (drawings, bills of materials, test reports). If professional licensure matters in your region or for your intended role, check whether the education route aligns with local recognition or accreditation requirements, since licensure pathways differ worldwide.

Skills developed in mechanical engineering

The skills developed in mechanical engineering start with fundamentals, but become valuable when you can apply them in ambiguous situations. Technical foundations include stress and deflection, vibration basics, heat transfer, fluid behavior, and energy conversion. Over time, you learn to translate these concepts into constraints: allowable stresses, safety factors, thermal margins, tolerances, fatigue life, pressure losses, noise limits, or efficiency targets.

Equally important are method and tool skills. Many engineers use CAD to communicate design intent and ensure manufacturability, and use analysis tools (spreadsheets, scripting, or simulation software) to check whether a design meets requirements. You also build practical skills such as selecting materials, specifying fits and tolerances, planning tests, and interpreting data. Professional skills round out the profile: writing clear technical notes, presenting design trade-offs, collaborating across disciplines, and making decisions that prioritize safety, ethics, and traceability.

A helpful way to measure progress is by what you can show, not just what you have studied. Examples include a documented design iteration, an analysis report that explains assumptions and boundary conditions, a test plan with acceptance criteria, or a failure investigation summary. Even for early-career engineers, learning to keep design files organized, manage revisions, and write concise engineering reasoning is often a differentiator, because these habits support reliability and auditability in real projects.

Engineering workforce requirements and career paths

Because engineering workforce requirements differ by industry, many employers look for adaptable fundamentals plus evidence you can learn tools and processes quickly. To support that, some globally recognized organizations and platforms provide structured learning resources that complement university study or on-the-job development.

| Provider Name | Services Offered | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| ASME | Courses, webinars, standards learning | Industry-aligned professional development and standards context |

| Coursera | Online courses and certificates | Broad catalog with projects across engineering-adjacent topics |

| edX | University-level courses and programs | Academic depth with assessments and structured sequences |

| MIT OpenCourseWare | Free course materials | Full lecture notes and assignments for core engineering subjects |

| SOLIDWORKS | Official CAD training | Tool-specific workflows and practical CAD skill building |

| Autodesk Learning | Training for Autodesk tools | Structured tutorials for design and documentation workflows |

| Siemens Learning Center | Training for Siemens software | Focused modules for Siemens engineering tool ecosystems |

In day-to-day work, workforce expectations often cluster around three themes: solving open-ended problems, collaborating across functions, and delivering traceable results. Design-focused roles emphasize requirements, concept selection, CAD, tolerancing, and design for manufacturability. Analysis-heavy roles emphasize modeling assumptions, validation against tests, and communicating uncertainty. Manufacturing, quality, and reliability roles often prioritize process understanding, root-cause analysis, statistical thinking, and documenting corrective actions.

Career paths usually begin broadly and become specialized with experience. Early roles may include design engineer, manufacturing engineer, test engineer, or field/service engineer, each offering different exposure to products and constraints. Over time, engineers may move toward systems engineering, project leadership, technical specialist tracks (thermal, structural, acoustics, mechatronics), or industry niches such as medical devices, energy, automotive, aerospace, or industrial equipment. Across these paths, a consistent advantage comes from pairing strong fundamentals with a clear record of practical work: projects that show how you define requirements, choose methods, check safety implications, and learn from test feedback.

Mechanical engineer training is most durable when it is staged: build core engineering fundamentals, practice applying them through documented projects, and deepen into a specialization that matches your interests and local industry demand. Whether your route is a degree, workplace learning, short courses, or a blend, the goal remains the same: reliable problem-solving grounded in physics, clear communication, and repeatable engineering judgment.